Life In A Cat

Goodbye stranger, it's been nice

Eleanor lived to be 20 or 21 years old. Or maybe a little older; impossible to know for sure, as she was already an adult when I brought her home from the Chicago Anti-Cruelty Society in 2007.

I’d wanted a kitten; there were no kittens at the shelter— just unglamorous adult cats. Their cages were arranged in a grid, like the Cell Block Tango number in Chicago if all of the women were napping while they justified the murders they’d committed. Each cage had a laminated page zip tied to the door giving biographical details about the cat contained therein.

No dogs, please. No kids, please. Quiet home, please.

I was poor, insecure, and listless, 23 years old, and working for a financial services company that was actually an insurance selling operation. It wasn’t a scam per se, but there were better things that most clients could have been doing with their money. The company made itself seem legitimate by hiring celebrities to star in its national TV ads.

My office shared a building with a California Pizza Kitchen and was a short walk away from where they were just finishing up demolishing the high rise Cabrini Green projects. I hated the job. I needed the job.

I never felt like my situation was as precarious as it was, but maybe I should have. Before I’d had this miserable job, I’d participated in medical trials in order to make money. For one of the trials, I was given a mystery pill, sat watching movies for 2 hours, and then was asked to perform tasks that required me to wager pennies. Later I found out that the drug I was taking was for Parkinson’s Disease, and that other people who had taken it had claimed in a lawsuit that it had caused them to compulsively gamble.

The job was more a sales job than a finance job. I do not have the makeup of a person who can be good at sales. I always had trouble unquestionably believing in the value of anything, and I’m a bad liar.

A few times a week, I’d go out to area businesses and deliver “free lunch” to people whose business cards had been drawn from a fish bowl left next to restaurant cash registers. While the lucky winner and 10 of his closest coworkers scarfed free Jimmy John’s, I’d deliver a canned sales pitch about the incredible work my company could do for its clients. Of course I could go into more details if attendees would only share their names, addresses and phone numbers with me so that I could contact them for a follow up. Once I had inevitably failed to convert them into clients—they were in it for the free sandwiches— those names, addresses and phone numbers would be input into the company’s database, where people like me would hound them with sales calls forever.

On the day that I met Eleanor, it was cold and the ground was splattered with dollops of dirty March snow. I could not have been more depressed. I’m a rule follower, but that day, I left my office without telling anybody where I was going. My boss probably assumed I was doing a lunch n’ learn like the employees who truly had a passion for selling fixed annuities. I made my way to a no-kill animal shelter across the street from a Rock & Roll themed McDonald’s.

An animal shelter was a dangerous place for me to be that day. I’ve always loved animals and I’ve always been a sucker. When I’m depressed, these two traits are even more debilitating. I grew up less than a mile as the crow flies from my grandparents, and they had farm animals that lived in a barn, and the barn had a small colony of feral cats. Some of my most formative childhood experiences involved taming them from when they were kittens, or the agony of one of the cats I’d tamed falling victim to an indifferent tragedy of rural life.

As I was examining the cat cages at eye-level, I felt a little poke on my leg. I looked down and saw a small dirty cloud-colored paw extended through the bars near my ankles, a single curved nail snagged into my favorite pair of Express brand Editor Pants. I crouched down to look at the culprit. The cat in the bottom row looked me directly in the eyes, and meowed as loudly as it could.

It was not a musical meow— it was raspy and grating (later, I’d call it her “dinosaur meow”), but she was beautiful– a little white-chinned brown tabby with big green eyes, missing one of her front fangs.

Her laminated biography didn’t provide much information. Her name was Diamond (unclear if that had always been her name, or if it was just a name the staff had given her). She was two years old. She had been at the Anti-Cruelty Society since November of 2006. Her owners had surrendered her because she was too expensive. I did some math in my head. That was a long time to be in a cage that small.

I asked the volunteer if I could hold her. The volunteer took her out of her cage and I cradled her like a baby. She had a little nub where her tail should have been. When I went to pet her head, she bowed the top of her head into my palm, where it fit perfectly, and purred.

Then she wrapped her front paws around my arm and used both of her back legs to kick my arm, like I was a mouse she’d hunted, and she was trying to break my neck. The volunteer apologized.

As I was driving home with this strange animal in the cardboard box with perforated holes on the front seat of my parents’ green Dodge Intrepid, I decided her name was not Diamond. It was Eleanor.

I wondered how long she’d be in my life. The euphoria of freeing this little creature from a small cage was wearing off, and the reality of the commitment I’d just made set in. It was like the final shot of The Graduate.

She was two years old, and I was twenty-three, and cats can live to be in their teens, and I was going to be young forever. She might be there by my side until I was in my 30’s. Maybe even longer. What would she witness? What did I want her to witness?

When I brought Eleanor home, George W. Bush was the president. I would not have a smartphone for several years (late adopter). My first photographs of her were taken with a Blackberry. My favorite band was The New Pornographers, which would, in the ensuing years, lead to an endearing love of Neko Case.

Those early years, Eleanor would preside over the kitchen from the top of the cabinets. She would sporadically be overcome with aggression at night and attack my feet beneath the covers, or gently paw my face. She’d aggressively burrow next to me, run as fast as she could from one end of the long apartment to the other, springing to a window sill at the last minute.

She’d sit in the kitchen window and watch rats and squirrels (but mostly rats) run across the vacant lot next door, and then she’d watch the construction workers turn the bare ground into an ugly grey condo building, and then she’d watch the wall of the condo building, which sat vacant for years before anybody bought in (now, every building in Wicker Park looks like that). She’d sit in the window in the living room and wait for me to come home. I could see her compact silhouette sitting up there like a little statue every evening when I put my key in the front gate.

I never called her “Eleanor.” I called her “Kitty,” which evolved into “Pretty.” I don’t think she knows that her name is Eleanor.

I would let her roam free in my Dodge Intrepid when I drove from Chicago back to my parents’ house for the weekend. She would stand on her back legs in the passenger seat and meow at passing cars, a freeway star during rush hour traffic on the Kennedy. Weary commuters and travelers would smile and wave at the cat in the front seat.

I turned 25.

I had a different job, a slightly less embarrassing job, but one that unfortunately had me perpetually terrified that I was about to be fired. It was in downtown, which was a better commute than to the then-hinterlands River West.

The housing market crashed. One weekend in September, the company I worked for was acquired under duress by another bank. I got in shouting matches about politics with an old male coworker.

I was excited to vote for Barack Obama for president, and on election day, I left work a little early so that I could line up for the Obama rally in Grant Park. The amount of joy and optimism felt unstoppable. Eleanor was waiting for me when I got home.

My boyfriend lost his job in the ongoing turmoil of the financial crash, and moved in with me to save money, which Eleanor loved because that meant that there was a person to bother at home all day long. She’d sleep on his bookshelf while he studied for the CFA exam. She shed her undercoat on his desk. She spilled his Magic: The Gathering cards all over the living room, because his card box is where he kept his marijuana, and Eleanor loved the smell of marijuana. Which in retrospect might have been why she liked him so much.

My office phone rang one morning, with a 715 number I recognized. My had grandpa died suddenly in his sleep. I flew up to the funeral.

I became depressed. For about a month after the death, all I wanted to do after work was watch Twin Peaks in the dark of my bedroom until I fell asleep. Eleanor was there.

She was there when I got home from the hospital in 2009, bleeding and crying.

Eleanor witnessed my rash decision to fix whatever had led me to that point by picking up running in the middle of winter, and the mania that drove me to train for my first marathon. She saw me so behobbled by that race that I had to walk down the stairs backwards.

She played in the dust bunnies he left all over the floor of the office-turned-second bedroom when my boyfriend moved out.

She watched me decide I was going to be a writer. No more soul-crushing finance jobs. Now, onto a different kind of perpetual soul-crush that’s less lucrative.

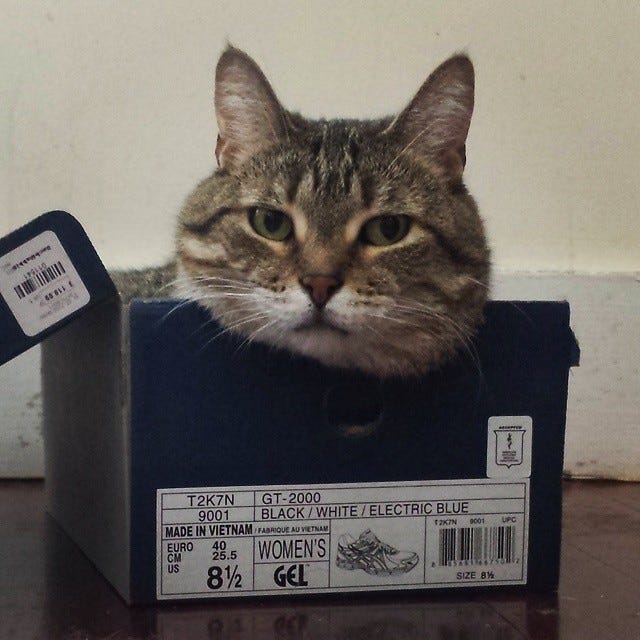

She cuddled up against me when I worked long shifts writing blog posts on Sundays for $100. She posted up in the doorway to the living room, forcing me to take breaks to feed her. She slept on the other, vacant pillow on my bed. She played in the boxes when I packed everything up to move to Brooklyn.

She played in the boxes when we moved from Cobble Hill to a gut rehabbed pearl factory two blocks from the gates of Greenwood Cemetery in one direction and with a view of the Statue of Liberty in the other direction.

She watched me celebrate my first TV writing job and declare I was leaving digital media forever. She watched me hate my first TV writing job and return to digital media.

She bullied the much larger cat male belonging to my partner. She licked her front paws as we loudly fought, and pissed all over his ties when the hanger holding them fell to the floor of the closet.

She waited there for me when I moved out, and eventually joined me in a sublet in Park Slope that spring when I alternately self-medicated and cooked elaborate salads. (After my ex handed her carrier off to me in the middle of 7th St, he returned to the pearl factory apartment and sent a tweet to my employer noting that I’d gotten fat.)

Everybody would ask why Eleanor didn’t have a tail; I didn’t know. The Anti-Cruelty Society said that it was amputated, but they didn’t know the reason. Whatever actually happened was probably lost by the time she’d halfway crossed the country with me. My best theory, knowing her, is that she tried to run out of a door that was almost closed and had her tail caught and broken.

She was an escape artist. She loved running out of open doors. She got caught in dressers, she was found wandering in the stairway.

In East Williamsburg she had two human roommates, one of whom she relentlessly bothered like a sister. She sat in the lone window in my room and watched the sky change color at night and waited for me to come home from wherever I was. She went through a phase of aggressively pissing on my bed because I was spending too many nights away, and I was so annoyed that I almost got rid of her.

I turned 30.

I started dating a comedian. I spent a lot of time going with him between bar shows, which I didn’t mind. I got to meet a lot of funny people, and a lot of strange people. I pressured him into getting his own cat. I think it’s still alive. I still miss that cat.

My other grandpa died. My flight to the funeral was canceled because of weather.

I’d feed Eleanor before I left for my 5 am Saturday long runs that zigzagged across the three bridges and up the west side path. I’d let her smell my face when I came home caked in dried sweat several hours later.

She caught her only mouse in that apartment, and was so switched on by the experience that she peered, crouching next to the stove, staring at the exact spot where the mouse had emerged from, for weeks after it happened.

She made a secret nest in my roommate Hayley’s closet, but when all of us were home she’d sit out in the living room on the little couch and purr loudly from the cushion she’d sit on like it was her own private pedestal.

My maternal grandma died.

I got a better writing job, I moved into my own apartment in Harlem. Every morning Eleanor would crawl under the covers with me, or sit on the end of the bed and wait for the brown pigeon – I called it The Enemy Pigeon– to land on the fire escape.

I started traveling to the west coast for work. When I was gone, my friend Emily would stay at my place and send videos of Eleanor pawing at birds on the TV.

Most nights I would come home and make myself a little dinner, exactly what I wanted to eat, and Eleanor and I would sit together and I’d watch television or read or get a little bit of writing done and have a beer. Eleanor would sit on a round grey pillow next to me that fit her body perfectly. I was no longer interested in living with men. I was pretty sure I wanted everything to stay exactly this way forever.

I began dating a Fort Greene Cat Guy who doted on her. He was an illustrator who drew her in a variety of impossible scenarios– dressed up as Amelia Earhart for Halloween, sitting in the window of a brownstone.

Donald Trump won the election, and the Cat Guy and I stayed up all night discussing moving to Canada while I struggled to meet a deadline. Eleanor was always a nonjudgmental witness to whatever was occurring in her space. As long as people were there to hang out with her, and as long as she had food to eat, she was happy.

Eleanor watched me make stupid decisions. Dangerous and reckless decisions. She watched me pack the biggest suitcase I could find and leave for Nepal. She waited for me for six weeks while Emily took care of her.

I returned, bruised, about 15 pounds lighter, my blood acclimated to the Himalayas and my brain clear. The Cat Guy and I stopped dating, and became friends.

I’d come home from hits on cable news, wearing silly little dresses in primary colors and camera-ready strip lashes. Eleanor would be waiting on the welcome mat. I’d peel off the strip lashes and toss them to the floor so she could pretend she was killing them.

I got a job writing for a TV show in Los Angeles. I found out I’d gotten the job one February morning, and that freezing cold evening, when I returned to my apartment, the seasonal affective lamp and down winter jacket I’d ordered were waiting in the lobby. Eleanor stayed in New York with the lamp and the jacket.

In LA, I lived in shitty AirBnB’s and took Ubers everywhere because I didn’t have a drivers license. To not have a driver’s license in Los Angeles is to have a voluntary disability— but skipping a northern winter was nice. I hiked up to the Griffith Park Observatory most days. I listened to a lot of Mitski. I missed taking the train. I missed everything about The City except the cold.

I came back East after the writers room was over. Eleanor had gotten really into batting at pictures on the TV with her paws, which made it difficult to resume my pre-LA nighttime TV ritual.

Los Angeles gradually claimed more and more of my time. I knew it wasn’t justifiable to keep my apartment in Manhattan. I packed up all of my furniture good enough to keep and put it in a storage pod to ship west. Eleanor watched, confused, but not worried (when she’s worried she pees on things). I found subletters to move in who agreed to look after her for a couple of months while I figured out my living situation. (It was a pretty good deal for them; the rent in my place in Harlem was an astoundingly low $2,000 a month. In 2018.)

I turned 35 alone in an AirBnB in Koreatown.

Earlier that night, I’d gone out on a bad date with a guy who I’d later run into several more times in Silverlake over the next few weeks, but after that never saw again. I wonder if he died.

I met somebody on a dating ap. We stayed out too late on a Sunday night and by the end of the month after my birthday, we were boyfriend and girlfriend.

I found my own place, a one-bedroom with a balcony and a walk-in closet. It was so much less stressful than trying to rent something in New York. Now that I’d given into the way things were, everything felt easier in Los Angeles. I was living in the nicest place I’ve ever lived. Sun poured into the windows from sunup to sundown. My boyfriend lived across town, in Silverlake. I spent a lot of time in a car.

I flew back to New York to get Eleanor in September. The subletters told me that hours before I arrived that day, she parked herself by the front door of the Harlem apartment, like she knew that I was coming. I was worried that she’d have a hard time with the long haul flight, but it seemed like she was just happy that I’d come for her.

She loved the big bright place in Hancock Park. I would let her sun herself on the balcony while I got ready in the morning, she’d roll around on the carpet on the floor of my bedroom. She stretched out on the dining room table.

She met my boyfriend’s dog. He liked her; she didn’t like him.

I boarded her before we took a trip to Italy, where Josh asked me to marry him. When I went to pick her up from the boarding kennel, she was huddled in a metal cage in an odd position. She was caked in waste, and her eyes were dull. She hadn’t eaten in days. I think she was too stressed out to do anything.

Clutching her to my chest and crying so hard that I was incoherent, we drove to a veterinary clinic. She peed all over me on the car ride. They told me that they didn’t know if she’d survive the night. She survived. Over the next weeks, I spent hours every day trying to get her to eat. I wrapped her in a towel so that she wouldn’t scratch me when I gave her medicine. I learned how to give her subcutaneous fluids myself, so I didn’t need to keep taking her back to the vet.

She recovered, and for years after we referred to the incident as “the time got so mad we left her that she tried to die.”

We moved in together, to a place on top of a hill in Echo Park, not far from Dodger Stadium. The house had a big window in the front room that the sun would sing through every morning. We could see the lights from night games. Eleanor sat in the window and watched people pass us from several stories below, meowing if she didn’t like the look of them.

She and the dog would sometimes sleep on opposite ends of the couch. A few times, we almost got them to touch. The house had a little back patio with a small tree, and I’d sit out there with her while she rolled in the dirt. Once, she nearly scaled the fence at the edge of the yard.

My other grandma died. She’d had brain cancer for years that nobody had known about. The tumor had made her mean and cruel, and because of how she’d treated my mother, I hadn’t spoken to her in a decade. I called her hospital room as she lay dying and told her that I was living in Los Angeles and about to get married, and that I loved her. She couldn’t speak.

I hadn’t driven a vehicle since 2009, but because I’d previously had a license, the state of California authorized me to drive on its roads after I passed a written test. I couldn’t believe how reckless that system is. No wonder there are so many accidents.

Eleanor loved parties. She loved circulating, like a slightly standoffish hostess.

The pandemic hit. They closed playgrounds and hiking trails. There was nothing to do but play video games, drink, watch Homeland, try to learn as much as possible about epidemiology, and cook.

We were home all the time, and were willing to wait an hour to get into Trader Joe’s to buy groceries. Josh got really into making Korean food. We befriended the personal trainer I’d hired to help me get in shape for the wedding we’d been planning.

We had to cancel the wedding. By summer, we were about to lose our minds, and so we hit the road for the desert. We took the dog with us. Eleanor stayed back in the little house on top of the hill with a catsitter, yelling at anybody who dared walk by on her sidewalk.

We got married.

The Dodgers won the World Series. We walked down to the intersection of Sunset and Lemoyne and watched cars do donuts and kids in the neighborhood set off fireworks. We got to go margaritas as the bad fish taco place on the corner that has since closed down and walked home in the cacophony. It felt like the end of the world.

Joe Biden was elected president.

We dressed the dog up in a Christmas sweater and Santa hat and looked at the lights in Burbank.

We drove out to a mountain town in Utah and rented a cabin. Eleanor had to stay home, but the entire time we were there Josh pitched bringing her next time. I kept seeing places that she could crawl inside and get lost.

I got pregnant. One morning, I woke up bleeding. Eleanor sat with me while I waited for my appointment at the doctor’s office, petrified. The baby was fine.

I’d read that cats can tell these things, but she didn’t really seem to care about my pregnancy with my first daughter, beyond the fact that my body was engorged with extra blood and thus I was a warmer thing for her to lie down on.

Right before Halloween, Eleanor had to have a procedure at the vet and was put in a cone. The night we returned home, our dog woke us up, and I discovered that Eleanor had escaped out of the window into our coyote-ridden back yard. I ran outside, hugely pregnant and wearing a tee shirt, calling for her. I found her trying to climb under the fence at the edge of the yard. Into the night, to certain doom. I brought her back inside. The dog got an extra treat.

I had a baby. The baby was born with a dislocated knee that bent in the wrong direction. We learned from the ensuing orthopedics appointments that babies don’t have kneecaps; human kneecaps don’t grow in until the children are 2 or 3. My daughter somehow got tangled up in an odd position inside of my body, and popped her knee out of joint, and then it just started growing that way.

When Eleanor first saw my daughter after we brought her home, her eyes got huge, and she bolted into another room.

I found that Congenital Knee Dislocation only happens in something like one of every 100,000 births. A hundred years or so ago, babies with the condition had a promising future in circus freak shows. My daughter got put in a leg brace that she had to wear constantly.

Eleanor was curious about jumping into the bassinet, but never did.

We moved again, to a house with a small yard.

Josh got really into decorating the house for Halloween.

I had no idea how to garden in our USDA zone, but I spent almost every Saturday at a plant nursery in Pasadena trying to figure out what I could grow. I tried to grow a watermelon plant in a container. I had no idea what I was doing. I found a sick Aloe plant the previous tenants had left behind and planted it in the bare between the sidewalk and the road. Eleanor would sit in the front window and watch me try to figure out what to do with the yard, watch our neighbors walk their dogs past the house.

The cat and the baby became friends. Thanks to the brace, the baby’s leg stopped bending the wrong way. She learned to walk.

The baby became a toddler. Eleanor would sit nearby when my daughter played. My daughter learned to be gentle with the cat. Eleanor would follow her around.

The toddler had a hard time with separation. She would wake up in the middle of the night and cry, and I’d go pick her up from her crib and bring her to bed with me; it was just easier than getting her to go back to sleep in her own space. Eleanor was banished from the bedroom.

The aloe plant, against the odds, became enormous, the size of a countertop microwave. The watermelon plant produced one single baseball-sized watermelon, and died.

I turned 40.

The toddler learned to run.

I got pregnant again.

Eleanor wasn’t as interested in playing as she used to be. She’d started doing enough territorial shenanigans that we had to keep her out of certain rooms in the house. She started sleeping with my husband every night, on the pillow next to his head, because the bedroom had become a fraught toddler sleep zone.

Eleanor still hissed at the dog but stopped acting like she was worried he might eat her. She would drink out of his water dish as a way to assert dominance over him.

The aloe plant became monstrous, the size of a residential dishwasher, and started sprouting satellite aloe plants on the formerly barren dirt.

Our dog got sick. He got better. I wondered which of our pets would go first. I worried about what would happen if they went at the same time. I worried about what would happen if they didn’t go at the same time.

I decorated the house for Christmas in a manner that I reluctantly describe as “Griswoldian.”

I seeded the median and the grass with native California wildflowers I’d bought from a website, so that after the rainy season is over, the yard would become a meadow and a habitat for pollinators. I asked for and received a string trimmer for Mothers Day. I wasn’t listening to much music anymore.

Eleanor kept getting sicker. Her bloodwork told us she had kidney disease. All cats get it if they live long enough. She became obsessed with Josh. Josh bought a stroller that most people use for dogs and started taking her on walks.

I had my second baby. This one was born en caul, which means inside the amniotic sac. And unlike the startling backwards-leg situation with the first one, an en caul birth is considered lucky. I didn’t think to ask them to keep the membrane my daughter was born inside; if I’d been a poor Brit in the 1800’s, I could have sold that thing to a ship’s captain for a lot of money.

Eleanor had already seen a baby before, so this one didn’t freak her out as much.

The baby started smiling when she was only a couple weeks old. She was one of the happiest babies I’d ever seen.

Eleanor started losing weight. She constantly had the sniffles. We were going to the vet a lot. She got put on a special diet. She started sneaking into our older daughter’s room and setting up camp on her bed.

My older daughter started preschool. Every day after being dropped off, she’d wail so loudly that I could hear her from the parking lot. She stopped wearing dresses, she stopped favoring her tricky knee. She asked to be Flounder from The Little Mermaid for Halloween.

Donald Trump was elected president, again.

The baby started crawling, and reaching for Eleanor. Second children are fearless in a way that occasionally seems demented. The baby did not fear getting scratched by the cat and grabbed for her with the confidence of a snake handler. But rather than attacking the baby (which she would have been well within her rights to do), the cat learned to avoid her.

The baby learned the word “gentle.” The cat would sit there nervously while I guided the baby’s hand to her head or back, before deciding that enough was enough and fleeing to higher ground.

The baby started walking, and babbling. The baby would sing to the cat, because she’d heard me sing to the cat. The cat would spend most of the day sitting in the window waiting for the sun, or chirping at neighborhood cats.

Eleanor was getting old. She would trend sickly for weeks. I’d worry that she was coasting toward the end of her life. Then she’d make a miraculous turnaround, launch herself over the dog in a feat of acrobatics, attack a reflected beam of sunlight across the floor.

She stopped bathing herself. Her hair became clumpy, and then she started pulling it out. We’d find little fields of it strewn across the floor in the morning. The vet said that she still had spirit and energy, and was just aging. One of her teeth randomly fell out of her mouth. The vet said that she needed most of her teeth extracted.

I called my friend Alyssa crying about the cat.

Eleanor had so many ups and downs that it started feeling silly to bother Alyssa with my fears that I thought it was over. The Cat Guy who I’d dated back in New York would reach out occasionally and ask how she was doing, and more than once I’d told him that I thought the cat was dying. He sent me a pillow he had made with Eleanor’s face on it.

She was almost dying— no wait! She was back. Every time she came back, she was like her old self, except a little less. No more rolling around lustily in a sun-drenched spot on the carpet. No more burrowing into bed with me and purring against my stomach. The raspy meow faded to a whisper. One of her eyes would swell up, her sniffles would get so loud that you could hear her from the other side of the house. She wasn’t running jumping anymore. She didn’t care to hiss at the dog. But she had so many unlikely recoveries that I thought that maybe she’d just continue getting better, over and over again, forever.

Days would go by when I hadn’t spent time interacting with her much, apart from feeding her. She wanted to be left alone to sleep. My presence would just attract the kids and the ruckus they brought with them.

We shut Eleanor into the office during our Halloween party. One of the kids let her out and I spent a panicked 5 minutes looking for her, only to discover that she hadn’t escaped into the night; she’d just been eating.

The baby turned into a toddler. The preschooler turned four.

Eleanor is no longer beautiful in a conventional sense. Her fur is dry. She has no teeth. She still has one big round green eye, but the other eye is always swollen.

Her back legs wobble when she walks. She doesn’t seem to know where she is all the time. She enjoys sitting next to Josh, but she has stopped sleeping on the pillow with him. She stays in a small side room.

I looked at the website of a home euthanasia service, and called the number. They will send somebody to your house, they told me, and the doctor will stay with you for up to an hour. They will give your pet a sedative so that they comfortably go to sleep, and then after they’ve been sleeping for a bit, they will administer the medication that stops their heart. You can hold the pet while they do this. “Thank you,” I said, “I will call back if I decide to make an appointment.”

I bought Eleanor a heated bed that seemed to make her joints more comfortable. She stays there most of the time. In the morning, if she can muster it, she gets into the front window and watches the people walk their dogs. But it got harder for her to jump. Sometimes her back legs wouldn’t cooperate.

I took my older daughter to her doctor’s appointment and held her while they vaccinated her. I promised her that because she was brave, we’d get ice cream after school.

After the appointment, a strange feeling came over me. I called the pet euthanasia phone number service from the car and scheduled somebody to come to our house on Saturday. They reassured me that I could cancel up to four hours before the appointment without a penalty. They asked if I wanted her remains returned to me. I said yes.

That night, as I was getting the girls ready for bed, I couldn’t find the dog. He’s usually on his bed in the living room. But he was sitting in the office, next to the cat’s bed, head up and alert, like he was watching out for her.

The next day, I took Eleanor to the vet and dropped her off for some bloodwork, because I wanted to make sure I wasn’t making a mistake. As I arrived at the vet, a white car was leaving, and a black van that said “Pet Aftercare Services” on the side was pulling in. A man got out of the van, walked around to the back, and took out a large white cooler on wheels.

I explained Eleanor’s situation to the receptionists at the front desk. I kept crying, which embarrassed me, because I could see in their microexpressions that they found it annoying.

The man with the cooler wheeled it into the back of the vet’s office. And then he wheeled it back out to the van, lowered a ramp, and wheeled the cooler into the back. The man drove away.

Later that day, when I came to get Eleanor, the doctor took me into an exam room alone and told me that the humane thing would be to let her go. Her organs are failing. She’s very sick. If we hospitalized her, she probably would not survive. He asked if I wanted the printout of her lab results. I put them in my bag without looking at them.

I sobbed with relief and sadness. I wanted clarity. I’d gotten clarity. I wanted assurance that I was doing the right thing, and now I knew that I was. It felt fucking awful, but not as bad as not knowing.

I waited in the lobby while they prepared some pain relief medicine to make her more comfortable for her last few days. It was the same lobby where I’d clutched her to my chest after the Italy trip, blocks away from that sunny apartment Eleanor loved so much.

I stared out the floor-to-ceiling windows with my cat in her carrier at my feet.

When I cradle her now I can feel all of her bones. I can feel her spine and her ribcage. How did so much life fit inside such a tiny frame?

She will let you know, friends said.

On Thursday morning she was splayed out on the floor in the office, unable to find the strength in her back legs to stand. I picked her up and set her back in her bed and made a phone call. It was time.

A pet sees everything you hide from the world. A pet doesn’t get to witness any of the self that gets shown off on a resume or Instagram grid. A pet loves you anyway.

They hold that dark piece of your humanity in them, quietly, like a diary that can never be read. And that broken, sad, imperfect you that they’ve seen— when you’re alone in your apartment and you’re hiding from your landlord with the lights out because you can’t afford to pay your rent until your paycheck hits in three days, when you’re giving your body to somebody who is not worthy of you, when you’re throwing up or bleeding or masturbating or passing out in the clothes you went out in the night before— that fucked up person is their perfect world. They don’t need you to be anything other than there for them. When they’re with you for long enough, they know you more than any person ever will.

She knew me more than any person ever will.

The night after the doctor told me that it was time to let her go, I wake up at 2 am. I give up on trying at 4 and stumble to her bed in the dark. She stirs and opens her mouth as though to meow, but no sound comes out. I reach out my hand. Like the day I met her, she pushes the top of her head into my palm, where it still fits perfectly.

Queen of Queens ♥️

This is so beautiful and so full of love. I have so enjoyed hearing about Eleanor on Hysteria over the years. It was always clear how much she was loved and how much she gave you too. She was one spirited lady. You must all be heartbroken. Love and sympathy to you and your family. I hope particularly that your wee ones are ok. I imagine your older girl understands a little more and the first experience of death is a hard one.